By Jim Garamone DoD News, Defense Media Activity

PRINT | E-MAIL | CONTACT AUTHOR

WASHINGTON, March 21, 2017 — By April 1917, people were already calling the war between the Allied Powers and the Central Powers the Great War, and they were right to do so.

Millions of soldiers confronted each other on the battlefields of France and Russia with thousands dying each day, even when there were no big offensives.

And on April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on the German Empire, joining France, Great Britain, Russia, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Italy. They were arrayed against Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria.

Both sides expected a quick and relatively bloodless victory when the war started in 1914. By the time the U.S. joined the fight, the population of whole nations had dedicated themselves to winning the war. Millions of men were growing ever more proficient at using new technologies to kill each other.

The names of the bloody battles in Europe were already well known to Americans, as a corps of outstanding war reporters from the major newspapers covered combat and sent back daily reports. The Somme, Verdun and Tannenberg resonated in the United States, just as they did in Europe.

France had a long scar running across it where millions of German, Austrian, French and British soldiers lost hundreds of thousands of soldiers for gains measured in yards. Russian soldiers, tired of the war, were joining revolutionaries calling for the end of the war. Russia’s Czar Nicholas II had abdicated in March, and while Russia continued to fight, it was half-hearted. Fighting was ongoing in Italy, the Balkans, Mesopotamia (now Iraq), Palestine and Africa.

Such was the situation on April 6, 1917, when the United States formally declared war on the German Empire and joined the Allied camp.

Zimmerman Telegram

President Woodrow Wilson had campaigned and won re-election under the slogan “He Kept Us Out of War.” He was sworn in for his second term on March 5, 1917, but already the man who was “too proud to fight,” was revising his thinking.

“Wilson truly wanted to stay out of the war,” said Brian F. Neumann, a historian with the Army’s Center of Military History and the editor of the service’s series on the war. “To his thinking, if the United States had to enter the war, then it had to be for more than just maintaining the status quo.”

Diplomats in Europe called the United States “The Great Neutral” and U.S. envoys worked to affect a peace on the continent. But on Jan. 31, the German ambassador to the United States delivered a note to American officials stating that Germany will begin unrestricted submarine warfare. This meant Germany would sink without prior warning any ship sailing near Great Britain, France, Italy and in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea.

“This is not as shocking today as it was a century ago,” Neumann said. “The Germans were scraping the bottom of their manpower barrel and they saw isolating Great Britain as their best chance of knocking the country out of the war. Americans regarded this as another example of German brutality and their desire to make war on civilians.”

Wilson was gobsmacked, and the next day he severed diplomatic relations with the German Empire, but stopped short of seeking a declaration of war.

At the end of February, Wilson learned of the Zimmermann Telegram. This is a telegram intercepted by the British from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann to the German ambassador in Mexico City. The telegram instructs the ambassador to offer the president of Mexico — with whom the United States had a strained relationship — Texas, Arizona and New Mexico if his country declares war on the United States.

U.S. officials confirmed the telegram was authentic and released it to the press on Feb. 28. The American people were enraged, and Wilson ordered merchant steamers to be armed.

‘No Selfish Ends to Serve’

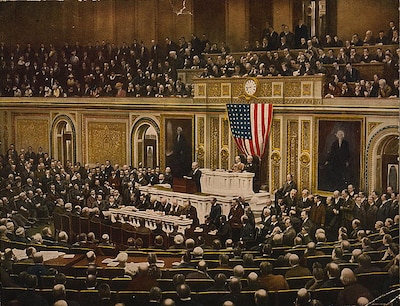

In the next few weeks the German U-boat campaign sank three U.S-flagged ships and that campaign was intensifying. Wilson called for a special session of Congress to meet on April 2. On that date, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany.

“Woodrow Wilson was a very reluctant warrior,” Neumann said. “[He thought] if Americans are going to get involved in the quarrels of Europe, it had better be for a greater good.”

The president saw the war leading to the dissolution of empires, and leading to self-government.

“The world must be made safe for democracy,” Wilson said in his address to Congress. “Its peace must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty.

“We have no selfish ends to serve,” he continued. “We desire no conquest, no dominion. We seek no indemnities for ourselves, no material compensation for the sacrifices we shall freely make. We are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind. We shall be satisfied when those rights have been made as secure as the faith and the freedom of nations can make them.”

Four days later, Congress sent the declaration of war to Wilson for his signature.

A Different America

Both the Allied and Central Powers realized the power the United States could bring to the war. The population of the United States in 1917 was roughly 103.3 million. Of those, about 15 million were foreign-born and there was great concern that these “new Americans” wouldn’t fight for the nation. There were, after all, hundreds of German-language newspapers in the United States, serving more than 2 million people who had been born in the German Empire.

Most Americans — 55 percent — lived and worked in rural areas. Farms had little mechanized assistance. There were still good careers for farriers, smithies and farm laborers, as horses and mules still supplied much of the motive power in and around the United States.

Highways were small and any long-distance trip was on a rail car pulled by a steam engine. Aircraft were still so new that people would come from miles around if one landed in a nearby town.

Telegrams were how most people got news from relatives far away, but telephone lines were growing. Radio — then called wireless telegraphy — was a promising new technology. Moving pictures — movies — were discounted by many as a passing fad.

By law, women could not vote. By practice, in many places neither could African-Americans or other people of color.

And there were divergent opinions on the war itself, Neumann said. The United States had a large number of Irish immigrants with little love for Great Britain.

“Millions more from Eastern and Southern Europe had come to the United States to get away from the arbitrary rules of aristocracies,” he said. “But still, by 1917, a good-sized majority of Americans saw the need to enter the war on the Allied Powers side.”

American Might

The United States was a game-changer. America was an industrial colossus. In 1900, the U.S. Steel Corporation alone, made more steel products than all of Great Britain. Henry Ford’s Model T and his assembly line efficiencies meant the day of the horse and buggy were fast becoming a thing of the past. Industrialization of agricultural processes would mean fewer laborers needed on farms and more needed in factories.

The United States had a literate and growing workforce and that combined with the mass production of things and the means to transport those things were revolutionizing America.

The United States, in short, was a country of tremendous potential, and so was its military.

The Great War was conflict on an industrial scale. Men were as interchangeable as cogs in a machine. Millions manned the trenches and millions more behind the lines supplied them and still millions more made the instruments of death.

The U.S. military wasn’t even remotely to that kind of level. The U.S. Army had a grand total of 121,797 enlisted men and 5,791 officers on April 6, 1917. The Army was spread at posts around the American West and on constabulary duties in the Philippines, Puerto Rica, Cuba and Panama.

The Army had few machine guns, no heavy artillery, few planes, no tanks, little munitions, few trucks and vehicles.

The National Guard had a grand total of 181,620 personnel and they were cursed with uneven training and even older equipment than the active force.

The Army had not organized into divisions since the Civil War and most officers knew little or nothing about moving and fighting large formations.

The Navy was little better with about 300 ships and 60,000 sailors, but the Royal Navy really did rule the waves then and the need for U.S. seapower was not as critical.

On April 6, 1917, few could guess what role the American military would play in The Great War. But the declaration of war itself, marked America’s long stride to the center of human events. America and Americans were unprepared, but willing to make the sacrifices.

It would take time for American military power to grow, learn and mature, but it would be decisive in The Great War.

(Follow Jim Garamone on Twitter: @GaramoneDoDNews)